DJ COMMUNITY

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the legendary New York City club Giant Step. To celebrate we took a look at the club’s ’90s heyday, hearing from the voices who lived it.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the legendary New York City club Giant Step. To celebrate we took a look at the club’s ’90s heyday, hearing from the voices who lived it.

by

Vikki Tobak

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the legendary New York City club Giant Step. To celebrate we took a look at the club’s ’90s heyday, hearing from the voices who lived it.

By now, hip-hop’s lineage with jazz, funk, and soul has a well-trodden history. From being highly sampled in golden era classics to its deep association with producers like DJ Premier and Pete Rock, jazz fueled a love affair that would forever change the path of music.

In the New York City of the early ’90s that love affair came to life at a dimly lit underground club called Giant Step. Aptly named after the seminal John Coltrane album, Giant Step was more than just a weekly club night. It was a musical mecca for a burgeoning hip-hop contingent including The Roots, Erykah Badu, A Tribe Called Quest, Massive Attack, The Fugees, De La Soul, Jamiroquai, and many more. It was the place where hip-hop stood on the shoulders of jazz, offering younger generations to see heritage artists like Roy Ayers and Gil Scott-Heron play to a room full of kids from Brooklyn and Queens who just got off the train listening to the latest hip-hop in their headphones.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the legendary club Giant Step, a space that would essentially become a think tank for music heads rooted in jazz, funk, hip-hop, and all things black music. For the occasion, we talked to a number of figures who were. They provided insight about the glory days of Giant Step.

Main Players (Alphabetical Order)

Alice Arnold — photographer who shot many nights at Giant Step

Maurice Bernstein — Giant Step co-founder

Gary Harris — former EMI A&R executive; Harris passed away in 2018 from natural causes

Jazzy Nice — Giant Step’s second DJ

Mark Ronson — producer who started his DJ career at Giant Step

Jonathan Rudnick — Giant Step co-founder

Louie Vega — a Latin house DJ who spun at Giant Step during the ’90s

Ron Trent — former resident DJ at Giant Step

The Beginning

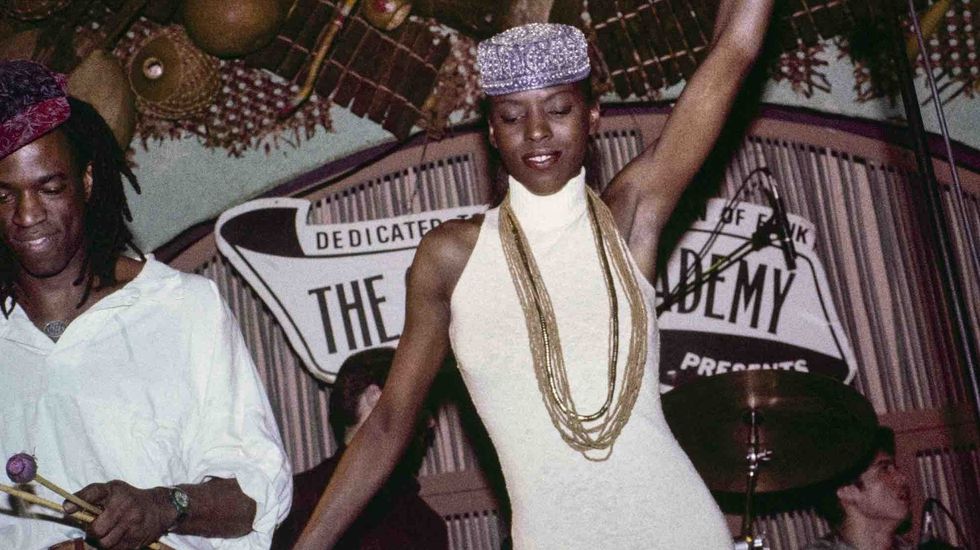

In 1990, The Groove Academy, the umbrella organization that would launch Giant Step, was formed, with a mission “Dedicated To The Preservation of Funk.” Founded by a British promoter named Maurice Bernstein and his South African counterpart Jonathan Rudnick, Groove Academy promoted live shows while Giant Step was the weekly club night dedicated to funk and soul culture.

The jazz hip-hop crossover sound was new to the states and the Groove Academy crew quickly set out embracing artists early in their careers and allowing them a stage to experiment and interact in a live setting with music heads who knew their history and were hungry for what was to come. Every Thursday night, somewhere in New York City, live musicians playing alongside DJs, creating a very New York moment.

Jonathan Rudnick: Groove Academy was the mothership that started it all out to garner respect for funk and funk attitudes. The stars of the ’70s — although they were highly sampled — were not getting the recognition. [They] weren’t being presented in a live forum. So, we started off with Maceo [Parker], Bootsy, George Clinton, the Ohio Players and that was the Groove Academy. Out of that sprang the jazz-oriented street wing, Giant Step [with] Giant Step being a moveable club environment and then just sort of an environment in general, wherever it lands. We wanted to create a like-minded network not just in America, but around the world.

Maurice Bernstein: Many of the artists we booked were looked up in the phone book, as many of them were not working or had agents. Artists like Bootsy Collins, George Clinton, Ohio Players — we wanted to bring them to play in front of new fans who only knew their music from hip hop samples. None of them had agents then, we’d just call them up at home and say, “are you interested in doing a show with us?”

mish-mash of sounds

While The Groove Academy staged concerts with Maceo Parker, Roy Ayers, and other legends, the new generation of club kids were seeing hip hop’s golden era come to life in front of their eyes at Giant Step. The weekly club — which was originally at S.O.B.s before moving to venues such as Metropolis Café, Supper Club, Sweet Jane, Bhudda Bar, Shine, New Music Café, and the Village Gate — was an experimental place where live instrumentation and musicianship was respected and remixed along with turntable skills and sampling. Some started to call the new scene Acid Jazz or hip-hop jazz. But to the dancers gyrating on the dimly lit dancefloors, it was nothing less than freedom. The scene drew artists who felt the club was a laboratory for experimentation: Guru’s Jazzmatazz; Digable Planets, and Buckshot LeFonque debuted at the club while overseas counterparts like Jamiroquai, Galliano, and Massive Attack broke new music in the states at Giant Step events. Giant Step was influential in opening up that global conversation while also getting American groups who played at Giant Step to play British music festivals.

Gary Harris [in an interview conducted in 2017]: Giant represented an amalgam of what was going on in New York Black music at the time. All around the city at clubs like Nell’s, Frankie Jackson’s Soul Kitchen, and Giant Step, club culture had almost a deep church feeling. When I was working with D’Angelo, the nuance and subtlety that was coming out of the music at Giant Step was in line with so many artists of that neo-soul movement and even groups like De La [Soul] and [A Tribe Called Quest.]

Louie Vega: I DJ’d at Giant Step at the same time I was at Sound Factory, two clubs that were very music forward. Giant Step was known for rare Groove jams and it was a really special moment because you could hear the original records that hip-hop was sampling from. You could feel that Giant Step was first and foremost about the music. They mixed genres, which is a very defining moment for New York. The scenes were converging and you had Biz Markie hanging out with house head kids… the worlds of New York collided. Which was something we learned from the generation before us, folks like Larry Levan at Paradise Garage and David Mancuso at The Loft. Music brought us together from different walks of life.

Harris: The clubs were very influential in creating this loop of sample records that were being sampled on new records by the next generation of artists. The DJs would dig for these rare records and the producers and artists would be in the space listening. It was competitive and that breakbeat culture was amazing. The DJs at Giant Step played the originals and then some nights you even got to see the artist perform live.

The vision for Giant Step

Giant Step was also providing a conversation between New York and what was happening in England with the Rare Groove and soul scene at the time. Bernstein grew up in the north of England, and was inspired by the Northern soul movement, a movement that incorporated elements of the British mod scene and Black American soul music. Bernstein and his friends became students of American soul music from cities such as Detroit and Chicago and the scene gave way to a specific kind of club and DJ culture. The competitiveness between Northern Soul DJ’s to unearth rare records by lesser-known artists and rare releases was the stuff of legend. In an effort to keep their record finds secret, DJs would cover up the labels on their records and spend hours digging for records only they had.

Meanwhile in London, rare groove and Soundsystem culture was raising a new generation of club kids. Norman Jay’s High On Hope at Dingwalls and Gilles Peterson’s Sunday Sessions at the same place brought together funk grooves with Jamaican Soundsystem elements with early dance music, setting forth a music forward environment rooted in club culture. Collectives like Jazzie B’s Soul II Soul and Paul Anderson’s Trouble Funk were pure magic. When Bernstein arrived in New York, his love for this type of music culture informed his vision for Giant Step.

The funk and soul renaissance going on at Giant Step and Groove Academy seemed inevitable in many ways. The style and swagger of Coltrane and Miles Davis and [Charles] Mingus mixed perfectly with the new confidence of curiosity of hip-hop. Jazz, funk, and soul was the perfect database for hip-hop’s growing interest in Afrofuturism and Black consciousness and sounds of the past generations.

Bernstein: When I came to New York, there there were no jazz dance clubs catering to the kind of rare cuts I was a fan of. There were no rare groove clubs. The first one that I found that was anything close to what was happening in England was Frankie Inglese’s Soul Kitchen where Frankie played classic grooves and rare stuff. Soul Kitchen was the thing that gave the confidence to do the Groove Academy, which was bringing back the artists whose records Frankie was playing.

The thing I noticed about the New York DJs, in contrast to the Northern Soul crew, is that New York DJs knew how to cut records. DJ Smash was our first DJ and he could mix, cut, scratch, and be more New York with it. Hip-hop culture was of course big on cutting during that time so that was important to us. We wanted to create something where the music is incredible, which was a tremendously naïve way to try and start a party in New York, because nobody gives a shit. We didn’t care about the men-to-women or bottle service or any of that. We only cared about the music. So, by starting it like that, we struggled for a long time. You’d get a couple of music nerds coming to your party. It wasn’t really until we found a nice moody venue, which was in the basement of the Metropolis.

Jazzy Nice: I played quite a few what you’d call jazzy record — Roy Ayers and Donald Byrd and those kinds of records. Those were New York. Songs like [Roy Ayers’] “Everybody Loves the Sunshine” and [The Blackbyrds’] “Rock Creek Park” — those are New York anthems. You could play it right now and people will love it. And all those records came very organically at Giant Step.

The era of rare groove is produced so well. That’s why drum breaks and songs like [Keni Burke’s] “Keep Rising To The Top” and [The Gap Band’s] “Outstanding” and [Mary Jane Girls’] “All Night Long” will be sampled forever. Those kicks, some snares in those songs…. it’s just so phat. And they just sound wonderful and they never get old. You could kill a dance floor with these songs still, even to a younger crowd.

Mark Ronson: I grew up in New York and played in school bands and stuff like that. One day, I went into Tower Records. I bought [The Best of The Meters], [an] Average White Band [LP], and, I think, The Best of the Ohio Players, or maybe The O’Jays. And I just suddenly was like, “Whoa, I really love this music.” And it was about the same time that the Brand New Heavies came. And the Brand New Heavies was really eye-opening. I was like, “I can’t believe people can make this music, now.” They were being promoted by Giant Step.

One night, I just remember Bob Gruen, the veteran New York photographer who was a friend of the family, took me and my friend Sean [Lennon] around during New Music Seminar. We went to see a bunch of random shows — Barenaked Ladies, and just weird shit. But I remember just being like, “We’re gonna stay out ’cause we’re gonna see The Brand New Heavies at Giant Step. I hadn’t even started DJing and this sound I heard was just really everything that I wanted to be about. The following year, I asked Maurice to put us into one of their Giant Step showcases and we ended up playing during the music seminar with Arrested Development. I don’t know how we managed to get on that gig.

Linking back to the past

Emerging DJ’s like Ronson and groups coming up at that time, The Roots, Erykah Badu, Common were rethinking those classic groove songs. Hip-hop was number one but the link to the past was inspiring a new sound and a new alternative in hip-hop that diversified the genre beyond boom bap. The cache of funk and jazz godfathers were an inspiration to a new crop of artists on the verge.

Nice: We had so many producers and rappers, and MCs in the house at Giant Step. I’d hear the records that I played weekly later sampled on their albums. I think we all influenced each other. Clubs were so important in breaking new artists back then. For example, when Digable Planets were recording their debut album, I was the first person given [“Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat).”] I would just play the instrumental for like five minutes, just teasing the entire club and I would see the whole club going wild. Questlove used to be at Giant Step almost weekly. He drummed with me. This was even before the Roots got really big. It’s funny because I saw Questlove a couple of years ago and he gave me a very nice compliment. He said, “You know, Jazzy. I was there the night that you rocked the “Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat).” He said, “I want you to know that you were like one of my biggest inspirations in that moment.”

Ronson: There was a purist thing about those kinds of DJs and the Giant Step DJs and the English rare groove DJs as well. There’s such a lineage of this soul music. I would go to these record conventions. There were these big record fairs that happen every and now and then, and everybody was going around trying to find new breaks, and you would see everyone from Large Professor to Q-Tip and then those would land on records or in the clubs. I love to watch the crowd when you drop “Daylight” by Ramp (sampled on “Bonita Applebum” by A Tribe Called Quest), or a sample everybody loved, and see them like, “Oh shit, this is like the original.”

Even much later, like when Busta Rhymes had “Put Your Hands Where My Eyes Can See,” [which] was like the biggest comeback in New York for that year. Like to play the original Seals and Crofts “Sweet Green Fields” record… as it builds slowly into the loop, it’s kind of hinting that it’s going to go there, then… and the whole crowd [is] like, “What the fuck?!”

Views: 10

Comment

© 2025 Created by Janelle.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of NASTYMIXX to add comments!

Join NASTYMIXX